| Three artists of Auschwitz recall the years of horror

By Pat Healy

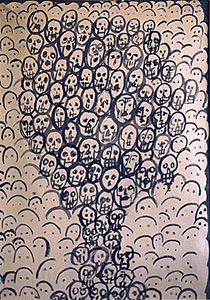

Józef Szajna drew pictures of his friends because it was the only way they could see what they looked like. As a prisoner at Auschwitz and Buchenwald concentration camps he was forbidden to have or use a mirror, he told an audience of more than 200 at Wellesley College this past Tuesday. Drawing was the only way he and his friends could see how thin they had become. " We didn’t know our own faces," the broad-shouldered Pole told the crowd through an interpreter. He paced back and forth, emphasizing his emotions with his hands. At a panel called "Artists of Auschwitz," held in conjunction with "The Last Expression: Art and Auschwitz," exhibit at the college’s Davis Museum, Szajna and two other Holocaust survivors spoke of the art they created while imprisoned by Nazis. The talk drew so many people that it had to be moved from the college’s 168-capacity Collins Cinema to a larger auditorium. Half of the art from the exhibit was actually produced at Auschwitz - either clandestinely or on command, while the rest was created by artists during the war at other camps throughout Europe. Because Jewish prisoners frequently did not live long enough at Auschwitz to create art, the vast majority of the Jewish work in the exhibition (with the exception of three artists) was created prior to their arrival at the concentration camp. Moderator Yehudit Shendar explained how many of the artists could not commit their work to any medium while imprisoned, that they would often draw on the backs of work assignments. "An artist remains an artist even when he can’t put things down on paper. He can think about art, he can imagine art, and the first moment that he gets the opportunity he produces art," she said. Yehuda Bacon, one of the few Jewish artists represented in the exhibition, committed more art to paper about Auschwitz after his liberation in 1945. Deported to his first camp in his early teens, he spoke on Tuesday about the drawings he did while in Theresienstadt, the ghetto for Jewish deportees en route to killing centers in the East, and the streak of documentary drawings he produced after his time at Auschwitz. His drawings during camp were of safe subjects like Eskimos and gypsies, but even these were done in secret. His drawings of the Auschwitz-Birkenau crematoria numbers 2, 3 and 4, disrobing room, and gas chambers, which he drew after Auschwitz, were entered into evidence at the Adolf Eichmann trial as prosecution exhibits T1318-1325. Bacon said art has helped him process the Holocaust into a lesson for others. "I thought in my naďve belief that if I could show them the sorrow, then people would change for the better," he said. "I thought that something had to be done with this experience and I tried the best I could to draw my memoirs and also as a teacher to educate and to tell this story in the hope that maybe somebody will learn from it in a positive way and we will be better human beings." Max Garcia was a diamond polisher before he was captured in 1943 and taken to Auschwitz. Garcia told Tuesday’s audience that he realized that a diamond polisher in Auschwitz was "not one of the favored professions," so he wrote on his entrance form that he was a carpenter, a profession in which he had no training. "While I’m in here, I thought I might as well learn a trade," he said. While not a visual artist, Garcia became a performer at an Auschwitz cabaret as master of ceremonies. Geared towards entertaining the SS, Hitler’s elite police, Garcia quickly learned how to gain the favor of the officers. "I began to learn German as if my life depended on it, which it did," he said. "because if you could speak German, you were less likely to have beatings, and if you had less beatings your chances of survival were greater, so everything was geared towards survival." A cabaret at Auschwitz? Shendar pointed out how that might seem odd to us now. "Can you believe that in that other planet named Auschwitz there was a museum? Can you believe that in that other planet named Auschwitz there was a workshop where artists produced art on command," she asked. Davis Museum Director David Mickenberg, curator of the exhibition was also a moderator of the panel. He said through some of this art we are able to understand the complexity of the atrocities these people witnessed. "Their experiences and perspectives present Auschwitz as a multi-faceted reality in the face of horror," he said Szajna’s work "Our Biographies" is an abstract piece depicting anonymous rows of prisoners. Their bodies drawn in pencil with thumbprints for faces, it has become the logo for the exhibition. He said the work was both a documentation of the loss of identity and a chance for his own immortality. "I decided that I had to leave my mark on the world," he said. "If I would perish in the camp I wanted something to live after I died." If you missed the "Artists of Auschwitz" panel discussion, you can still catch the concert, "Musik Macht Frie," held on Feb. 8 at 7 p.m. in the Towne Gallery and feature Wellesley College Chamber Singers performing vocal music from Terezin.The Davis Museum is open Tuesday through Saturday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sunday, 1 to 5 p.m. The museum is closed on Mondays and major holidays. From Jan. 29 through June 5, the museum will also be open Wednesday and Thursday until 8 p.m. For individual or group tours, call 781-283-3382. |

A Penal Company /SK/ and Typhoid Fever by Józef Szajna |